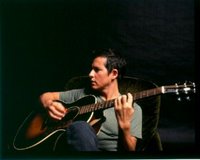

In 2005, producer Joe Henry created a body of work that not only included notable contributions to albums by Ani Difranco, Aimee Mann and Susan Tedeschi, but revitalized the careers of some of America’s finest soul singers, including Ann Peebles, Mavis Staples, Irma Thomas, as well as the lesser-known Allen Toussaint and Bettye Lavette. It is one thing when a producer helps a recording artist raise their game and deliver great work (as was particularly the case with Mann’s

The Forgotten Arm); it is quite another when a producer seeks out great artists for the particular purpose of delivering fresh and inspiring work that stands along their own substantial legacies (and perhaps raises their profiles in the process).

The latter has certainly been the case with

I Believe To My Soul, Vol. 1, a compilation of beautiful performances by Peebles, Staples, Thomas, Toussaint and Billy Preston that – though recorded prior to Hurricane Katrina – ended up being marketed by Rhino Records and Starbucks’ Hear Music imprint as a Hurricane Katrina benefit record (Toussaint and Thomas were among thousands of New Orleans musicians immeasurably affected by the hurricane and its aftermath). The project was the brainchild of Henry, who was actively seeking to revive Peebles’ career in particular, but the album soon evolved into a series of recording sessions with a revolving cast of soul greats (anchored by Henry’s own close-knit group of session players). The result is a brilliant reminder of how much talent still exists in the oft-ignored world of soul music (though all of these artists retain active careers touring to enraptured audiences all over the world). The project is reportedly the first in a series, and Henry is slated record a full record with Peebles. Furthermore, Henry’s friendship with Elvis Costello has apparently led to a full album project between Costello and Toussaint. For my part, Allen Toussaint has been a revelation, an artist who I’d really never heard of yet consistently delivers gorgeous performances (Henry and Toussaint also collaborated for two tracks on Nonesuch’s

Our New Orleans benefit record).

I Believe To My Soul by itself would be enough to justify heaps of praise for Henry, but you can’t ignore his substantial contribution to Bettye Lavette’s

I’ve Got My Own Hell To Raise, a project that more or less follows the same formula as Solomon Burke’s

Don’t Give Up On Me, an album that won both Burke and Henry a Grammy. Lavette and Henry hand-picked contemporary songs from the catalogs of better-known female songwriters (Lucinda Williams, Fiona Apple) and have given them a bluesy, gritty workover. Who’d have thought, for instance, that so much additional juice could be squeezed out of Lucinda Williams' “Joy” (also given a lyrical makeover, courtesy of Lavette). Though the record is solidly great throughout, Henry and Lavette should be credited with delivering two of 2005’s most transcendant performances with Joan Armatrading’s “Down To Zero” and Sharon Robinson’s “The High Road” (probably the two least-known songs on the record). If you want to measure the full potential of this pairing of artists, look no further.

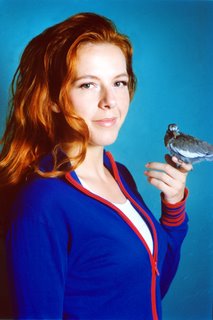

A similarly inspired pairing is evident on Aimee Mann’s

The Forgotten Arm, her first fully realized and uniformly consistent record. Mann’s previous work has always relied somewhat on studio enhancements, but for whatever reason, she decided to lean heavily on a more classic sound for this, her best record to-date. As such, Henry’s greatest contribution to the record seems to have been to simply filip on the tape and get out of the way (though here again, Henry draws heavily from his stable of studio regulars). The result is lean, yet muscular, anchored primarily by drums, bass and piano (though guitar and horns accent the proceedings throughout). Meanwhile, Mann is at her best vocally, imbuing this tale of doomed romance (the record is somewhat of a concept album) with a lovely and bittersweet melancholy. Mann deserves plenty of credit for the continued maturation of her songwriting and sound, but Joe Henry clearly brought something to the table as well.

Whatever that something might be, Henry clearly has become a much in-demand (if still under-the-radar) producer of choice for many artists. However, his role as “career revivalist” for some of the greatest soul artists of the sixties and seventies is where his impact is most accutely felt. My own fear is that his terrific solo work will take a backseat to his production work, but hopefully he’ll continue to strike a fine balance of the two, to everyone’s great benefit. Because what Joe Henry is doing – much of it outside the mainstream of the record industry – is building a legacy of work that generously and rightfully shines a spotlight on some of our greatest musicians, too often ignored or forgotten. Joe Henry has dared to remind us that some of America’s greatest voices still have something to say.

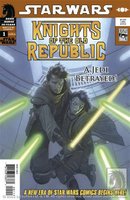

So the nerds at Bedrock City called to tell me that my box at the store was overflowing. While cleaning it out, I picked up a copy of this new Star Wars series from Dark Horse. Really cool idea, based on the same general timeframe as the video game series of the same name.

So the nerds at Bedrock City called to tell me that my box at the store was overflowing. While cleaning it out, I picked up a copy of this new Star Wars series from Dark Horse. Really cool idea, based on the same general timeframe as the video game series of the same name.